THE WOMEN TRYING TO SURVIVE

Understanding women-led environmental justice activism in southwest Detroit

By Anna Tropiano

December 15, 2020

Photo by Ali Lapetina for Bloomberg Businessweek.

“I got a granddaughter who is one-years-old. I want her to survive. I want her to be able to see the blue skies. I want her to see the green grass. I want her to be able to see an ocean. I want her to see fish swim in an ocean. People say you’re a community activist. No. I am just a human being trying to survive.” — 48217 resident Theresa Landrum.

T

he anxiety and stress was too high. So I said I wouldn’t watch any TV, and I asked everybody that called me, 'please do not tell me anything about the election.' So I just told one trusted person that I would call them when I was ready. And I just wanted them to say yes or no. And they said yes. So that’s who I was talking to when you called.”

I’m on the phone with Theresa Landrum, a life-long resident of one of the most polluted zip codes in the state of Michigan. About 20 minutes before our scheduled interview Joe Biden was officially called the winner of the 2020 presidential election; in the living room directly under where I’m sitting, CNN is still blasting into the house that I share with nine other University of Michigan students. Landrum and I have only been speaking for about 15 seconds, but I can already feel the distance between our lived experiences. The feeling reminds me of when I would wake up first at a sleepover with my cousin who lost her mother to breast cancer, stare at her sleeping form and wonder, if by touching her skin I could absorb her consciousness, what it would feel like to carry that weight.

Theresa Landrum also lost her mother to cancer—first diagnosed with throat cancer, then parotid gland cancer, and finally lung cancer in 1986. In 2007, Landrum received her own diagnosis. And then over the years, she lost neighbor after neighbor, entire blocks in her neighborhood wiped out from cancer. In an interview with a Washington D.C. nonprofit Friends of the Earth, Theresa said,

“Our neighbor Miss Lucille, she died of cancer. One of our friends, Rita, who was in her 20s, she died of cancer. Then another young lady Anita, she died of cancer. Delbert, he had a tumor in his neck that grew so big it looked like he had two heads. He was in college and they had to send him home and he eventually died from the cancer. Despite these things I hadn’t yet put it together.”

Growing up in Boynton, a primarily Black and lower-class neighborhood in southwest Detroit now more commonly referred to as 48217 by residents and officials alike, Landrum thought that the brown and rusty air she saw in the sky, often giving off a sick orange glow, was normal. What Landrum couldn’t have known at the time was that this concentration of death was not an anomaly. And the twenty-six industries that had sprung up like invasive weeds around her community over the years were not there by accident. Her community had fallen prey to a phenomenon called environmental racism: the disproportionate allocation of environmental hazards near the poor and people of color. In short, pollution may not discriminate, but polluters do.

Environmental racism happens all over the world. In my work as a researcher for the Department of State on an environmental defenders project, I’ve read case after case of how industries choose to place mass polluting projects near communities who they believe won’t have the political power to fight back. In Brazil, it’s indigenous communities. In the United States, it’s communities like Landrums’—Black, hispanic, and lower class—who bear the worst of the burden. But I’ve also seen how these marginalized indigenous communities in Brazil have organized to resist massive industrial powers at great personal cost—and sometimes win.

Similarly, the community of 48217 has labored extensively over the years to protect themselves and their neighborhood, from conducting their own research on emissions levels, to taking legal action. Planner’s Network, an organization of progressive urban planners, describes:

“Living in the shadow of industry, the 48217 community has familiarized themselves with the environmental regulations and planning policies that have worsened their air quality and decimated their property values... They are adept and strategic about organizing class action lawsuits, and they see through bureaucratic practices that allow industry to pollute with impunity. They also have a deep understanding of the science behind air quality measurements and the health impacts of such staggering rates of air toxins.”

48217’s work is a living definition of environmental justice, which, at its core, is a response to environmental racism. It’s a movement that has been historically led by the marginalized, and is unique in its ability to have joined several movements together at the hip, while always keeping people’s livelihood in focus. Dr. Giovanna Di Chiro, an environmental justice scholar and grassroots activist writes of the difference between environmental justice, and the mainstream environmental movement: “The merging of social justice and environmental interests, therefore, assumes that people are an integral part of what should be understood as the ‘environment.’”

But beyond this impressive collective action, there’s something even more striking about the community response in 48217. It’s tied to a much longer history, and a group that has gone unacknowledged and unappreciated for far too long.

THE EMERGENCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE IN 48217

The town of Boynton is located in southwest Detroit to the northwest of River Rouge and Ecorse, which border the Rouge River, a tributary of the Detroit River. It is split into two defined neighborhoods due to historical redlining: the whiter Oakwood Heights to the north, and Boynton to the south, which is home to Black and Latino communities. I-75 splits the two communities down the middle, and distributes its car exhaust equally to both.

When residents from 48217 are interviewed, they often speak about their town in the past tense, with hurt, anger, and nostalgia. In the 1940s, Boynton became a mecca for African Americans who migrated north to fill the jobs vacated by men who had left for World War II. By the 1950s and 1960s, the neighborhood had blossomed into a tight-knit community of families, caring teachers, local businessnesses, and flourishing lawns and gardens thanks to the boom of the auto industry. Isolated from the rest of the city due to racial housing segregation, 48217, then known as the Del Ray community, was nonetheless a chance at the American dream for the tens of thousands of Black people who had escaped the Jim Crow South. It was its own little utopia.

Zip code 48217's location in southwest Detroit.

But even by the 60s, the destructive cycle of industrialization and pollution in 48217 was already underway. In the 1920s the Rouge River was channelized to allow the passage of freighters to and from Henry Ford’s River Rouge Plant, and the Detroit Salt Company opened; with the 1930s came Marathon Petroleum refinery and steel manufacturing plants; in the 1950s the Detroit Edison Company (DTE) set up shop on the Rouge River; and in the 1960s the Detroit Water and Sewage Department opened for operation. Also in the 60s, the state built I-75 straight through the Del Ray community, forcing residents to move, and destroying the community’s wooded area and wetland where children played in the creek. The introduction of I-75 opened the previously isolated community up to even more industry. By the late 80s and 90s, Del Ray was unrecognizable. People were forced to put tarps over their cars parked in the street to protect them from the ash that fell from the sky from the nearby plants. And then people started to get sick.

Today, 48217 remains literally surrounded by heavy polluting industry giants. Five of them—Ford Motor Company, EES Coke Battery, US Steel, Marathon Refinery, and Carmeuse Lime and Stone, Inc, are within four miles of the area. In recent years, Marathon Refinery has encroached further and further on the community, eliciting a long and costly battle.

In 2007, Marathon Petroleum Refinery won a $2.2 billion expansion deal from the city of Detroit in exchange for the creation of 60 full-time refinery jobs and 75 full-time contractor jobs for Detroiters. The expansion, according to Marathon, would increase their heavy oil processing capacity by about 80,000 barrels per day, and its total crude oil refining capacity by about 15 percent—partially in preparation for the completion of the Keystone Pipeline, which at the time was still underway. “Heavy oil” is a gilded term for the high-sulfur Canadian crude oil from the Alberta tar sand fields known as bitumen: a thicker crude that requires more processing, and gives off more pollution. Despite this, Marathon also promised the city that the expansion would not increase their emission levels.

But this wasn’t true. As part of their expansion, Marathon had to apply for new permits from Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, (EGLE) which, according to Jorge Acevedo, a Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) senior environmental engineer, allowed Marathon to legally pollute the air with more emissions. From before to after the expansion, the limit on sulfur dioxide emissions, a pungent gas that irritates the lungs, rose from 178 tons per year to 371. The cap on particulate matter, which also causes breathing issues, went from 202 tons per year to 206.6. And nitrogen oxides, which can cause respiratory problems, headaches, chronic lung function issues, eye irritation, loss of appetite and teeth damage, went up by almost 300 tons per year.

Even if Marathon had been honest about their emissions goals, Michigan state representative Tyron Carter who lives near I-75 doesn’t believe it would have changed anything, per an interview with Bloomberg news this past October. According to Carter, state regulators rarely deny polluters permits in southwest Detroit. “They’d have a hearing, you’d go, you’d voice your complaint, you’d do it in writing, we as a community would show up, and then they’d get a permit anyway,” he says. The facts are on his side; since 2010, the MDEQ has approved 3,586 applications statewide and rejected only 18.

In the past three years alone, Marathon has violated state and federal air quality laws ten times. To provide compensation, EGLE proposed an $81,853 penalty for Marathon this past July, an idea that Landrum called “egregious” in its attempt to make up for what her community has been through. According to Wilhemina McLemore, Detroit district supervisor for the MDEQ's Air Quality Division, Marathon has never been severely penalized because they responded and corrected the violations quickly. This is a pattern that Denny Larson, Global Community Monitor's executive director, sees as a mistake. Detroit Metro Times reports: “‘Enforcement without penalties doesn't work,’ Larson said…‘There's a complete disconnect between what the state says and the experience of people who have to live along the fence line.’"

A woman named Rhonda Anderson has been fighting to end this disconnect for years. Anderson, a life-long resident of Detroit herself, is a highly decorated community activist who works as the Sierra Club's environmental justice coordinator in Detroit and with the residents of 48217 to mobilize resistance. In 2010, Anderson helped to initiate a collaboration between the Sierra Club's Environmental Justice Program and Global Community Monitor, an environmental group based in California, to assist residents of 48217 in conducting their own own air sampling studies. What they found was shocking, but not surprising.

Oakwood Heights resident Adrian Crawford had always been concerned about the smell of her basement, which had an acrid, chemical odor. She and other neighbors with similar complaints had visited the Detroit city council multiple times, but achieved no progress. After sending her samples away to be tested as part of Anderson’s program, she got a call from the lab saying that the levels of ethane and ethyl benzene in her sample were so unsafe that they recommended she evacuate immediately. Ethyl benzene is a well-known product of oil refinement.

Anderson contacted the MDEQ, but received radio silence. Thankfully, once Channel 7 news reported on the community’s findings, the EPA took notice and investigated. They found that Marathon had been polluting the city sewer system with their own wastewater. In response, Marathon installed a system to remove the waste and again avoided a fine by the city.

But the research and media attention the community earned from their studies helped to finally garner some concessions from Marathon. In 2012, Anderson advocated for the Oakwood Heights Property Purchase Program, an effort to get Marathon to buyout homes in Oakwood Heights on the north side of I-75 that the expansion would essentially build on top of. But while the white community was cleared and bought out, Marathon neglected to expand their deal to the Black neighborhoods of Boynton on the other side of the interstate, just a stone's throw away from the expansion themselves. In an article by the Sierra Club, Anderson described how the racial differences between the two sides of 48217 didn’t stop Boynton from rallying behind Oakwood Heights: “...the white and black communities really did work together. Oakwood Heights had the chance to escape, and they did.”

But what of Boynton? And what of the life-long residents of Oakwood Heights who refused to uplift their lives and move? "These communities become the sacrifice zones," said Leslie Fields, the Sierra Club's environmental justice and community partnerships director in Washington, D.C. in a Detroit Metro Times feature titled “In Marathon’s Shadow.” "They will never be availed of any kind of green, sustainable, clean future. This is where [industries] are forever going to be expanding."

A map created by 48217 activists marking the industrial facilities surrounding their community. 48217 is outlined in red. (Credit: Meg Wilcox).” Source: Environmental Health News.

THE RESIDENTS OF THE SACRIFICE ZONES

“This was not my life’s choice. In actuality, I didn’t like it. I was fearful too. I didn’t want to be the voice of the community. But somebody had to step up and somebody had to do it,” Theresa Landrum said to the audience, barely pausing for the applause before continuing with her story.

Landrum was speaking at the University of Michigan’s Rackham Auditorium for the 2020 Michigan Environmental Summit, a day for students, activists, and policy leaders to reflect on the past and the future of EJ work. The summit was held in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the 1990 “Michigan Conference on Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards," which produced significant progress towards outlining and achieving the goals of the movement in collaboration with the Clinton administration.

As I listened from the audience, Landrum gave a passionate account of her history with environmental justice, which began back in 1985 while she was still in college and working at General Motors as a mechanic. At the time, Landrum learned that the Detroit Salt Co. was planning to store toxic waste on its premises, and grew concerned that this would pose a danger to her community’s water source in the case of a flood, since her community 48217 sits below the water table of the local River Rouge. She visited her city council, who confirmed that they were considering the storage plan.

“So I went back, and I met up with a couple of the older seniors who had been in this fight and said, ‘well what can we do?’ And they said, when we go down there as a single person, it doesn’t work. So we came together as a group.” Theresa explains how she was chosen as one of three spokespeople, “Because everyone else was too afraid. And I said, ‘We can’t be afraid when they’re talking about poisoning something that we all need.’”

In 1999, the Detroit Salt. Co was sold, and granted a 20 year lease by the city of Detroit to excavate salt “right under our homes,” said Landrum. The excavation created earthquakes, sinkholes, cracks in windows and foundations. So Landrum formed another community group with fellow 48217 resident Dr. Dolores Leonard. They were successful, and the Detroit Salt. Co was forced to stop the blasting.

But although Landrum and her community were winning battles, the war was just beginning. Because in 2003, what’s now referred to as the “Northeast Blackout” shut down power across the Northeast and Midwestern United States, and parts of Ontario. For Landrum and her community, this meant that the pollution controls on the dozens of mass industrial companies surrounding her neighborhood went out of order. “And we found out that the only oil refinery in the state of Michigan, Marathon Petroleum Corporation, was emitting poisons to the heavens,” Landrum said to the audience. “Out of that came a lawsuit.”

While the surrounding suburban communities of Dearborn, Lincoln Park, Melvindale and Allen Park were placed under a mandatory evacuation, the city of Detroit did not evacuate 48217 and other Black neighborhoods in southwest Detroit. “And when we found a lawsuit had been filed by the white suburban areas, the African American community was not included in the lawsuit,” she said. Then when 48217 filed their own lawsuit, they faced another roadblock. “The judge would not allow us to sue on health,” Landrum said. “He only allowed us to sue on property damage….That was just a slap in the face.”

But the community was finally about to receive some help, via the arrival of the Sierra Club’s Rhonda Anderson. “She came to our community and asked could she be invited in,” Landrum said, growing emotional. “And we was like, ‘invited in?’ Nobody asked us if they could be invited in. People just do what they want to to us.” Landrum described how Anderson worked with the community to teach them environmental justice principles, how to organize, and do their own research: log the trucks that passed from different industries, how to take photos, identify different types of smoke.

Landrum grew to realize that self-reliance was their only option. She describes an attempt to seek help from the MDEQ as completely useless. “They leave it on the community to create data that we already know, and they’re failing us. Our lives are expendable to them. It took us to do a health survey, presented to the University of Michigan with Dr. Paul Mohai and Dr. Byoung-Suk to show that we have a serious problem before the MDEQ would even come and sit with us.”

Finally in 2015, Dr. Dolores Leonard, the retired professor who worked with Landrum to stop the Detroit Salt. Co blasting, was finally able to form a partnership with the MDEQ. Her asthma had grown so severe that she was forced to keep an inhaler in her purse, and on her kitchen table and nightstand at home. In 2015, she submitted a proposal to MDEQ to set up air monitoring stations in 48217, which was approved. As laid out in 48217 Community Air Monitoring Project’s official report, produced by MDEQ, Leonard then worked with Rhonda Anderson of the Sierra Club and the community to select representatives of various 48217 neighborhoods and a resident with prior experience in engineering. In December of 2015, a meeting was held between the community representatives, MDEQ staff, researchers from the University of Michigan, and the EPA to discuss the implementation.

The results from the stations confirmed what the community already knew: high levels of sulfur dioxide, and concerning levels of carcinogens naphthalene, arsenic and hexavalent chromium. The process taken to achieve this research demonstrates how a lack of a federal standard for environmental justice hurts communities. In California, for example, areas that score above the 75th percentile on their environmental justice screening tool called CalEnviroScreen, which measures 20 components of pollution and population vulnerability, immediately are marked to receive pollution-reducing investments. So if 48217 was in California, their levels of pollution and demographics would have automatically set off a chain of events in their favor. But in Michigan, communities are left to do the work on their own.

Theresa Landrum (far right) speaks on an Environmental Justice Panel at the University of Michigan. Far Left: CEO of the Detroit-based Green Door Initiative, Donele Wilkins. Middle: Chair and co-founder of the Anishinaabek Caucus within the Michigan Democratic Party, Andrea Pierce. Image Source.

A 48217 air monitoring station. Photo by Adam Reinhardt.

Emma Lockridge, a photographer and fellow 48217 resident expressed similar anger over the burdens put on her by the state and the industries in her community. On November 9, 2017 a group of 48217 residents gathered outside of Marathon, many carrying signs saying things like “#48217 Lives Matter,” and “Marathon Petroleum. Expand Buffer Zone—Buy More Homes.” They were all wrapped up in scarves and hats; it was clearly freezing. Still, Lockridge shouted forcefully into a handheld microphone above the wind: “They put in a 55 billion dollar, state of the art filtration system to protect themselves, while we sit over in our houses and can’t breathe...A billion dollars they added already to their big fat pockets...but they refuse to drop a few thousand over here so we can live. This is a wicked corporation.” Her words were met by the sound of many assenting voices who were there to support the additional buyout protest Lockridge had started.

Lockridge, like Landrum, took to the streets and began advocating for environmental justice in her community once when she realized that if she wanted to live in a safe environment she would have to do something about it herself. At a 2016 Congressional Hearing titled "Environmental Injustice: Exploring Inequities in Air and Water Quality in Michigan,” Lockridge testified about how pollution can hold fatal effects to communities of color like hers. She described how, with Marathon Oil literally visible from her window, the smell is so intense that she got into the practice of wearing a mask to bed and hiding under pillows and blankets to escape the chemical odor. Her mother died because of respiratory failure. Both her and her sister experienced kidney failure, killing her sister when she was 49. Her next door neighbor is also on dialysis, and the woman across the street was also on dialysis before she died.

Today, Lockridge is a leader of Tri-Cities United, a community organization based out of Michigan United which is a coalition of labor, business, social service and civil rights members all across Michigan. Tri-Cities United works to connect 48217 and its neighboring communities of River Rouge and Ecorse to support the work of local leaders. Dr. Dolores Leonards was also instrumental to its foundation, and Landrum is also a member.

Rhonda Anderson. Theresa Landrum. Dolores Leonard. Emma Lockridge. And so many more. The trend is striking. All of Detroit’s most active environmental justice groups are led by women, including Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice (DWEJ), the Sierra Club’s office of Environmental Justice, Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision (SDEV), the environmental division of the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS) and Michigan Welfare Rights Organization (MWRO).

Acknowledging that Black women are leading environmental justice movements is important not only because their work should not be thankless, but because studying how individual identity affects our desire and ability to participate in activism is crucial to understanding why certain people participate in movements, and others sit them out. In fact, social movement research for the past 20 years has focused on how individual identity must correspond to the collective identity of a group as a predicate for participation in a movement. As researchers Polletta and Jasper theorize, people participate in movements when “doing so accords with who they are."

To get a fuller picture, I spoke to Theresa Landrum and Emma Lockridge, who graciously gave their time to help me gain a better understanding of Black women’s connection to environmental justice in 48217 and beyond, and what we can do to support their communities.

BLACK WOMEN AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

“If you look at history, Anna,” Landrum said to me on the phone. “Who holds the household down? The woman. Who holds the schools down? Women. Most teachers are women. Who holds the churches together? Women. Who are the backbone? Women.”

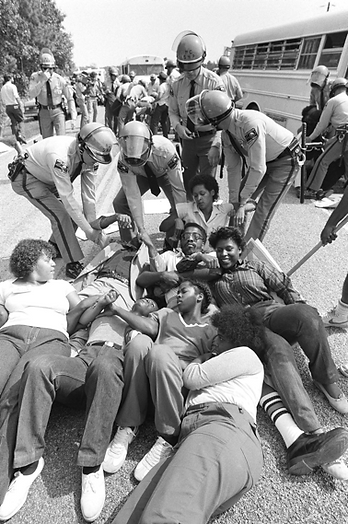

Black women have been at the forefront of the environmental justice movement since its inception. Historians trace the birth of the national environmental justice movement to 1982, when the state government of North Carolina chose the town of Afton in Warren County to be the site of a hazardous waste landfill that would accept soil contaminated with PCB, a dangerous chemical that had been illegally dumped on roadways. Residents, angry that state officials had dismissed their concerns about PCB leaching into their soil and drinking water, formed the community group Warren County Citizens Concerned (WCCC). WCCC staged nonviolent protests, including street protests, marches, and lying down in front of the trucks. It should now come as no surprise that Afton was the Blackest county in North Carolina.

The community received the support of civil rights organizations and leaders often in partnership with Black churches, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice. Over six weeks of protests more than 500 protesters were arrested—the first arrests made in the United States over a landfill. And although the residents were ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the establishment of the landfill, their work not only led to the creation of a loose network of environmental justice activists across the United States but monumental research. “Toxic Waste and Race,” the name of the 1987 study conducted by the United Church of Christ, found a “consistent national pattern” of race as the most significant variable in predicting the location of hazardous waste facilities. Rev. Benjamin Chavis, Jr., the United Church of Christs’ leader at the time, called the placement of the landfill in Warren County an example of “environmental racism”—coining the term for the first time.

Some versions of the story are told just like this, and end here: a terrible disservice. Because Warren County’s activism was not evenly divided—it was led by Black women. Black women were the first to make the connection between race and toxic hazards, and to ask why their county was chosen for the dump, despite being ninety ninth on the site selection list in clear violation of the EPA’s policy. Black mothers, especially, organized quickly and effectively to protect their children. And Black women were prepared to lay down their bodies and physical safety to make a statement about how the environment hurts them the most. Dollie Burwell, a participant in the Warren County protests, spoke about the women in her community’s unique role and burden in the movement:

“We had a protest where we made a conscious decision that only women would be arrested. Five women went to jail because we felt that not enough attention was paid to the fact that women and children were the most impacted by the dump. I don’t know why there are more women … but since slavery, women have had to look out for their children … this is the reality of my community’s church. The media could have defined this differently by showing the women and children who blocked the trucks. But the media wouldn’t focus on it … we were viewed as ornaments rather than leaders.”

When I interviewed Landrum this Fall, she told an eerily similar story about the work of Black women past, present and future:

“With the suffrage movement,” she told me, “Black women were deeply involved. But it’s not really publicized. They were very instrumental, but they were placed at the back. When white women marched for the right to vote, Black women were there. And as you look through the years, Black women were the last to have the privilege and the opportunity and the right to vote. Black women have always been the backbone—and just not black women but all women too—but even during slavery, it was the Black women holding up the master’s house and the Black man. And so I think it’s something that is innate, in a lot of women. Women were always told: ‘You stay in your place.’ Well women, they stood in their place, but, and I’m going to say this from a personal level, they learned that they have to outthink and outwit men. Especially white men. So, to connect this to the EJ movement, men have not had to be as tedious task masters, and I think that’s why women have come to the forefront.”

She continued: “Black women, many times when we’re in the room, we’re among white men. Talking to white men, the people who have been put into place to say ‘No.’ Or to refute data. All the years that we’ve been working in the EJ movement, before we had Lisel Clark,” Landrum said, referring to MDEQ’s current female Director, “We had Steve Chester, Dan Wyatt,” (former MDEQ directors.) “And when we were going into these rooms, into industry, we were dealing with white men. And it’s all because society has structured white men as the power force.”

What Landrum is talking about is a systemic issue. The marginalization of gender and rejection of Black women’s agency is pervasive not only in our national media—news coverage of Flint, MI being a prime example—but has been an issue within the environmental justice movement itself, an unfortunate contradiction to the movement’s goal. Environmental justice literature, policy, research, and activism rarely contain the gender perspective, which prevents all social groups from benefiting and ignores important areas of analysis.

It is even more damning then, that Black women, the agents of environmental protection, are uniquely harmed by their intersecting identities of gender and race. My mother is a birth doula—a trained professional who provides support to a mother before and after childbirth—so I grew used to hearing her rage at the dinner table about maternal mortality rates in the U.S., and how Black women are two to six times more likely to die in childbirth than white women, depending on where they live. “If someone tracked how many women of color have miscarriages,” Landrum said, “I bet it would be five, six times higher than a white woman.”

All identities, even the language that you speak can hold place in environmental justice. In Kettleman City, for example, a Spanish speaking, low-income hispanic community in the San Joaquin Valley in California, residents were unaware that a local agency was holding a public hearing to discuss the creation of a new body to manage the community’s often contaminated groundwater, because the agency failed to post a notice of the meeting in Spanish or file a Spanish version of their formation with California’s Department of Water Resources.

When I asked Landrum if she believed that men were connected to the fight in the same way, she responded immediately. “No,” she said. “No. No, they’re not. And that’s a hardship. Because we need all hands on deck because we’re dealing with a climate crisis.” She emphasized the last two words. “And we’re dealing with irreversible damage to our very being, to what supplies our air, our water, our food. And yes, there are some champions. But then look at all the old, white men who don’t give a shit about anything but their green dollars.” She apologized for cursing.

“But when you come to our meetings,” she said. “Majority women of color. Black, Latino, indigenous. It’s more women.”

An image of Warren County protesters clashing with North Carolina State troopers on September 17th, 1982. Source: Arcgis.com

A coalition of 48217’s environmental activists, majority women of color, showing their displeasure when all but one Democratic representative declined their invitation or failed to show at a meeting before the 2019 Democratic Primaries. Source: In These Times.

When I spoke to Emma Lockridge, she agreed that Black women have been the ones who have stepped up to the microphone in 48217, but also spoke fondly about Black men in the community who have provided support. “In our community association, of the united cities of southwest Detroit, Tri Cities United, we’ve had key men involved in this work and leadership roles.”

She continued: “I work part time as an environmental justice organizer at Michigan United, and two out of three of my supervisors have been Black men. I have the utmost respect for their work. And my first supervisor was so instrumental in helping me really up my motivations and dig deep so that I could be more effective.”

She says that young Black men have shown up at community meetings too, and that she often tries to make sure their voices are heard at events. “It’s a community problem,” Lockridge said. “And so all of us need to be involved.”

However, like Landrum, Lockridge spoke of how women are uniquely affected because of how the pollution is affecting their ability to have healthy children. “It is so distressing to me whenever I see a pregnant woman in our community, because I know she’s breathing our polluted air,” she said, telling the story of a woman in her community whose baby was born with severe asthma, and had to be hooked up to a respiratory machine. “The pollution is affecting children who are still in the womb.”

Both women also spoke about how Black men have been shut out from local industry jobs, while the officials who make decisions about their communities usually live 20 to 30 miles away. Although Marathon promised more jobs for Detroiters as part of their expansion, they never delivered. “We don’t have Black men in our community over there making those decisions,” Lockridge said. “I think that if [the officials] had to go to sleep and wake up with a terrible odor in their bedroom, or watch their children suffer with asthma, or had to go to the hospital because someone had some kind of cancer, I think it would be handled very differently. And so there’s a disconnect. That’s part of our challenge—to make them understand. I think that whether you’re talking about a polluting industry, or any kind of business, when people live in the community—you get a different kind of response.”

Landrum agreed. “Industry is very protective of who they let in. So they’ll let a few minorities in, but not too many. And that’s true today. So it’s hard because, right now, we’re still pulling teeth trying to open the door to let more African Americans in.” She connected this exclusion to larger social movements in the United States. “The two women that started the Black Lives Matter movement—it became about men, but it was started by women. The Me Too movement was started by a what? A Black woman. Then the face of it became a white woman. So African Americans are still being pushed out.”

“That adds such a layer of complexity,” I said, “that African Americans are being pushed out of the same jobs that are ultimately hurting their communities.”

“Exactly,” Landrum said. “That’s right.”

WHAT WE CAN DO

The fact that I am white and both Landrum and Lockridge are Black remained an undercurrent in both of our conversations, because of how interconnected systemic racism is with these women’s lives. “Systemic racism, economic racism, social racism, environmental racism, it’s all still the same,” Landrum said to me. Learning about how these systems of oppression work must be the first step. And then you have to do something about it.

“Do you know, we have fear when we leave our houses everyday?” said Landrum, her voice rising with every word. “We have to plan our route. Because when we go into Allen Park, Dearborn, we know that we are going to be racially profiled. And then 9 times out of 10, they’re going to pull you over. You know why? They know you can’t afford that high ass insurance that they’ve redlined on us. So you may not have insurance. So then that gives them an opportunity to what? Give you a ticket, take the car, make you go to court, pay a fine. And when you get to court, they tell you, now you have to go to driving school. It’s all a racket, a cycle to keep a race of people down.”

Oppression is insidious, and can sometimes be hard to spot. And that’s why it’s critical, regardless of what field you work in or plan to enter, to be on the lookout for it. Vicky Dobbins, Landrum’s friend who lives in River Rouge, shared how the doctor she saw when she was diagnosed with COVID directed the conversation toward her personal habits, as if her illness could be her fault. In an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, she said: “The doctors never ask you ‘Where do you live? What water do you drink? What water is around you? What kind of chemical are you ingesting?,’ ” she says. “They just ask you, ‘Did you smoke, did you drink, did you take drugs?’ ”

I asked both Landrum and Lockridge what would be the most helpful thing college students can do for 48217. Landrum’s first response was to ask that more people come to her community to learn about what’s going on. Landrum hosts what are called “Toxic Tours” in partnership with environmental justice classes at the University of Michigan, and for other interested participants. “We have become desensitized to it,” she said, referencing how tour participants often react to the conditions she lives in every day. “If you came down on a bad day, you’d be like, ‘Ms. Landrum, can I leave? I’m sick.’”

Lockridge, in addition, emphasized the importance of personal environmental accountability. What can college students do? “They can start with themselves,” she said, “and think about the carbon footprint you’re making.” And then it’s all about spreading the message of environmental activism. “You can encourage people you know, and start having conversations with them.”

But it’s the industries themselves that need to make the biggest changes. “During the start of COVID, when everything was shut down, I noticed such a change in the air,” Lockridge said. “It was like a miracle. I didn’t really want to go back. And now it’s bad again. But I was able to experience what it’s like—to wake up, and go outside, and the air is ok.”

So how does this change happen? By conversations between industry and the communities, a model that should be followed for anyone interested in helping communities suffering from environmental injustice. We can all look to Rhonda Anderson, the environmental justice advocate for the Sierra Club, who asked to be invited in and work with the community before she began educating and making recommendations. Any other way is demeaning to the community’s knowledge and agency.

“You have to join the people. Not come in and tell the people. We’ve had a lot of people down through the years come, and talk at us, not sit down with us. And we’re dealing with that with industry right now,” Landrum said. “I am on several advisory committees, and I have to be the one to say hang on, if we’re an advisory committee, what do we advise on? And if we say something, is it being taken to heart?”

This point of view was reflected by the community in Flint, MI affected by the water crisis. In 2016, Dr. Kent Key, Executive Deputy Director of the Community Based Organization Partners formed a writing group made up of Flint residents, grass-roots activists, community-based organization leaders and faith leaders, and researchers from Michigan State University and the University of Michigan. The group’s objective was to document Flint’s community’s story of the water crisis to elevate narratives that were not being heard by the media, especially African Americans whose work was being overshadowed in the media by their white neighbors. In summary of their views and what was expressed at community meetings, there were eleven key requests from the community moving forward that are applicable to how anyone who wants to help 48217 can observe.

All of the requests center around the same theme: community trust. Building trust with a community is a delicate process that requires humbleness, transparency, and respect for the community’s knowledge, data, and expertise. If you’re a journalist, attribute credit to those on the front lines. If you’re a volunteer, view them as partners. If you’re a researcher, prioritize the research they request. If you’re an official, give them a seat at the table. Give them the whole table.

And if you live on this planet, give some thanks for Black women. Thank the women of the sacrifice zones who are working for their whole communities, and for the good of our planet, and in the process just trying to survive. Thank them by showing up, by voting, by protesting. Thank them by calling your representative, by donating to good people doing the work. Stand up for them to send a message that we will fight for them the way they’ve always fought for everyone else.